Ahmad Alhamada welcomed Euroneus in his flat in Ghent, Belgium. Upon arrival, I was presented with a steamed tea pot, sliced watermelon and cashew nuts.

Originally from Idlib in northwestern Syria, Ahmad fled the country in 2012 during the reign of President Bashar al-Assad after the crackdown on anti-government protests.

The dramatic collapse of Al Assad on December 8, 2024 was at the hands of a surprising rebellion led by Ahmed Al-Sharaa’s extremist group Hayat Taharil al-Shara, once recognized as a distant dream at the forefront of reality.

The 30-year-old, who fled his country at just 18, had no idea that his evacuation would last for more than a decade, but was set to return to Syria in the near future to help rebuild his country.

Others have already begun a similar journey. Nearly 720,000 Syrians were deported between December 8, 2024 and July 24, 2025, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Of these, 40% have returned from Lebanon, 37% from Turkey, 15% from Jordan and 5% from Iraq. However, for Europeans, the desire to return home is rather low.

81% of Syrian refugees and asylum seekers on the continent, surveyed by UNHCR in May, declared they would not return to Syria within the next 12 months.

159 Syrians have voluntarily returned to the country from Belgium since January 1, 2025, according to the Belgian Federal Government Agency for Belgian Federal Asylum seekers (Fedasil).

The agency administers a voluntary return programme from Belgium to all immigrants’ countries of origin, whether they have denied asylum seekers, asylum seekers, or those without a valid residence permit.

These programs include transportation costs and travel assistance. For some immigrants, they may also include departure grants and support for reintegration in the country of origin. They can be used to help launch small businesses, pay rent and renovate homes.

And while these reintegration projects do not exist yet for Syrians, Fedazil is now making these grants available to Syrians looking to reunite with their hometown.

Rebuilding the country

Ahmad plans to return to Syria in a few years to help rebuild his country, if circumstances allow.

“There’s a lot to do. There’s a lot of needs in the country. There’s a good life here, but I think the country really needs support,” he says.

In his view, the priority is to disarm the militia and unite the nation. Once these conditions are met, Ahmad believes that most Syrians will “become back,” and will return their beloved hometown to the world map.

His project has not yet been realized, but he hopes to promote Syrian democracy through his association, the Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (DCHR). He added that Syrians living in Europe also have an intermediate role to play in reconstructing their own countries. “We can help European companies find opportunities in Syria, and we can help the Syrian government invest their businesses there,” he argues.

Ahmad was studying to become an engineer at the University of Damascus when the anti-establishment protests began in 2011. He co-founded the liberal student movement and took part in demonstrations against Al Assad, who was not shying to scorn him as a “dictator.”

“This country was like a prison, you couldn’t speak, you couldn’t have an opinion, you could have been killed if you were to,” he explained.

Expelled from the university, he was arrested and later imprisoned for three months at the infamous Sedonaya prison north of the capital Damascus, where he was subjected to mock executions and torture using electric shocks.

He was later acquitted by the court and released for his sole purpose by “building a room for other prisoners.”

With his newly discovered freedom, Ahmed chooses to flee Syria with his parents and siblings, settles in Lebanon, and is close to his country.

Lebanon has been home to Ahmad and his family for three years, where he opened a small shop in the name of Lebanese and participated in the initiative to open a school for Syrian children.

Lebanon has the largest number of refugees per capita in the world. The Lebanese government estimates that around 1.4 million Syrians have been displaced in Lebanon, of which more than 700,000 are registered as refugees.

Faced with the tragic economic crisis Beirut has been working on for many years and the rapidly deteriorating living conditions, exacerbated by the threat from Hezbollah, Ahmad decided to leave Lebanon.

“Lebanon has become even more dangerous for the anti-Assad, anti-Iranian, anti-hazbollah Syrians in the region. So we were also Hezbollah’s targets, and so were my family,” Ahmad says.

He boarded a Turkish boat, crossed the Mediterranean to Greece, and arrived in Germany, passing through North Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary and Austria.

He claimed that the taxi driver who took him and his two friends across the Serbian-Hungarian border had threatened them with a knife in the forest to force them to 2,000 euros.

After a two-week journey, he finally arrived in Belgium, and in 2016 he arrived at Brussels North Station.

Ahmad currently works in the IT department of the Administration and has dual citizenship in Belgium and Syria. He also founded the small association, the Centre for Democrat and Human Rights (DCHR), and was elected president of the association representing the Syrian community in Belgium.

When he woke up on December 8, 2024, sleeping Ahmad discovered that Bashar al-Assad had escaped the night before while watching his phone.

“It was a great day,” he recalls. He celebrated with the Syrian community all day long in the city of Brussels, and three days later boarded a plane in Amman, the capital of Jordan.

From there he took a taxi to the Syrian border, which he crossed on foot. Photos of the Al Assad family, usually on display at the Syrian border, have disappeared.

“There was only a Syrian flag, but that’s enough,” says the proud Ahmad.

The Border Post is currently home to soldiers from the Free Syrian Army, a coalition of decentralized Syrian rebel groups, and is currently working to maintain the country’s law and order. He recalls falling in their arms and crying with them: “It was a very moving moment,” he said.

Overwhelmed by emotions about what to do, what to do, where to go in his first reunion with his hometown 13 years later, Ahmad chose to set up his first stop at the university in Damascus.

“I was exiled, and now I’m back and Bashar al-Assad is gone. So for me it’s kind of justice and karma,” he rejoiced.

His reunion tour also marked notable stops at Homs, Hama, Aleppo, and his hometown of Idlib.

“I had to embrace each town, talk to people and walk the streets,” he says.

His return was filled with joy, but Ahmad also says it was a brave reminder of the misery that still lurks after years of oppression and atrocities.

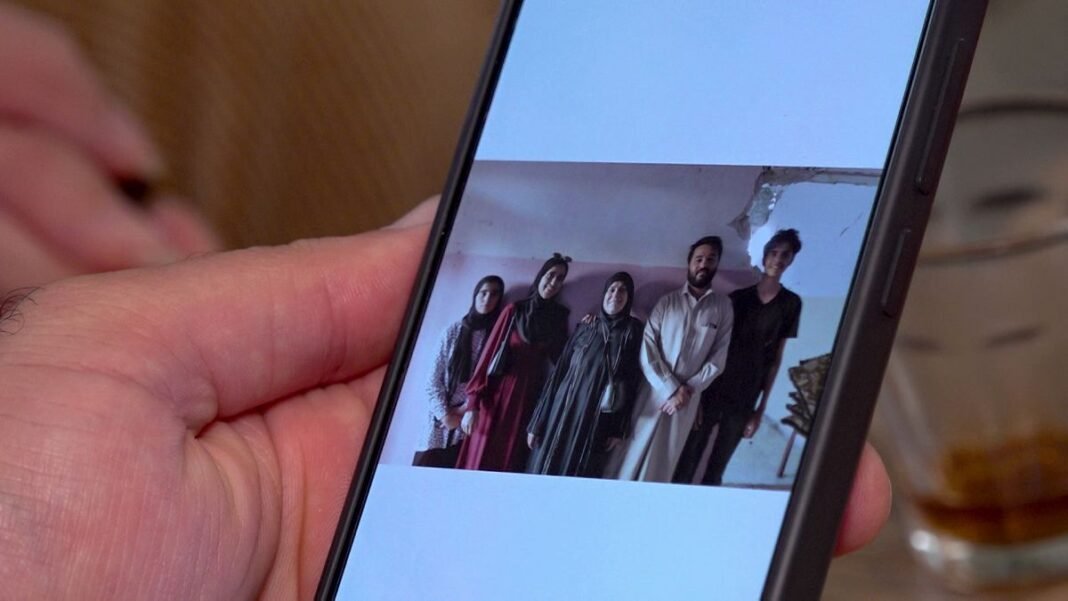

He says that many of the towns he visited were left in ruins, and the woman was holding a photograph in her own hands and looking for someone she loved. He joined a member of Idlib’s family, where he discovered that his home had been destroyed, just like in the rest of the city. He is planning to rebuild it now.

Staying in Europe

Aisha Abbas, 27, has been living in the city of Antwerp, Belgium since 2017. She originally came from Dirksh, a small town near Idlib on the Turkic-Syrian border.

When she hears the news of Assad’s collapse, she recalls Aisha, who shared that she has not slept for two days after hearing the news, “I couldn’t believe it. It felt like a dream.”

She regrets that her father, who “had spent his whole life in this moment” passed away before he had the opportunity to see it. Her first thought is that she can finally see the country in which she was born.

“I want to see the streets, I want to see people’s faces, I want to see how they live,” she said.

However, Aisha ruled out her permanent return to her country, mainly due to lasting uncertainty.

“How do you expect a place in the war for 14 years to be safe for people, that’s the battlefield,” she declared. “The collapse of government is not going to fix everything like a magic wand.”

At first, she doesn’t even know where to go.

“I don’t have a home. I don’t know if I can work or live my life. I don’t have any friends. Half of my family is dead. I’m even scared to think about visiting Syria and seeing places, but no one remains,” she explained.

After losing everything already, the first thing to do is to discourage her from coming back. She is determined to make life for herself in Belgium, whether it’s a “very international” place like Antwerp or somewhere “very quiet” like Ghent.

In 2011, Aisha’s father took part in a protest against the Assad regime. The Assad regime was heavily suppressed by the fallen president’s army and loyalty.

“We weren’t safe because he was a key figure in the revolution,” explains Aisha. That June, 13-year-old Aisha, her three brothers and mother, fled Syria and evacuated with her aunt to another bank on the Olondes River in Antioch, Turkey.

“I didn’t even pack my bags,” she recalled, “I thought I’d go back to September at the beginning of the school year.” Eventually, she resumed her “school” classes, which were open in flats by the Syrian community.

“We were living our lives here and we were really depressed for a year before we realised we had to build a new community to make new friends,” Aisha said.

Her mother held a small workshop where women could create and sell designs of dresses, crochet pieces, and handicrafts. The family stayed in Türkiye for seven years.

Aisha’s father finally arrives in Europe, crossing the Mediterranean by boat from Mersin to Greece in southeastern Turkey, and, thanks to Eu’s family unification, she arrives in Antwerp, where her family joins her by plane.

“Life in Turkey was really difficult for us and it wasn’t getting better. It was getting worse and worse,” explains the student. “He thought Europe might be suitable for school and work.”

The family of six lived in studio apartments before renting an apartment in the countryside.

“In Belgium, it was very different because I felt the way I dressed differently. I spoke. I didn’t speak Dutch. I always spoke English. I felt different.

Already Trilingal – she speaks fluent Arabic, Turkish and English – she easily added Dutch to the arsenal of languages and earned a degree in marketing and communications. To fund her research, she worked in a zero waste organic shop and gave pottery lessons.

This fall she hopes to earn her Bachelor of Communications and work in marketing and journalism. She is not given refugee status and has to renew her residence permit every year, and is about to acquire Belgian citizenship.

By the end of 2024, more than 6 million Syrians were registered refugees or asylum seekers, primarily in Türkiye, Lebanon and Jordan. The EU is home to approximately 1.3 million Syrian refugees or asylum seekers, distributed primarily to Germany, Sweden and Austria.

A day after Bashar al-Assad fled to Russia, many European countries, including Germany, Denmark and Austria, announced their intention to suspend further assessments of Asiram applications from Syrians.

Syrians closed their asylum applications in EU countries this year, figures from the European Union Asylum Agency (EUAA) report issued on September 8th.

The Syrians are no longer of a major nationality among the 27 bloc asylum seekers, currently ranked among the citizens of Venezuela and Afghanistan. However, the EUAA warns that certain groups of Syrians are still at risk of persecution.